Sometimes I receive a message or thank you note that truly makes my day. You know the ones—they’re the ones that make you realize that you made a difference to somebody. When I receive one of these notes, I get a little teary eyed, print it, and save it in a box in my office. One day when I retire, I’m going to take the box of meaningful notes and leave the rest behind.

What analytics really say about when to go for a two point conversion in an NFL game

The two point conversion has become more popular in National Football League (NFL) games, and it has become a popular topic of conversation in the NFL playoffs leading up to the Super Bowl. I once wrote a blog post that uses dynamic programming to identify when to go for 2 based on the score differential and the number of possessions remaining in the game. The analysis also shows what difference the choice makes, noting that most of the time the win probability does not make a huge difference in the outcome of the game, affecting the win probability by less than one-percent in most cases. In this post, I delve into the two point conversion, covering rule changes, football strategy, and assumptions.

By the numbers

In 2023, a typical NFL team attempted a two-point conversion about once 1 every 4 games and was successful just over half the time. A decade ago, a typical team attempted a two-point conversion about once 1 every 8 games and was successful just under half the time. Two point conversions became more popular and more successful. Two rule changes influenced these changes:

- In 2015, the NFL moved the extra point attempt from the 2 yard line to the 15 yard line.

- The proportion of extra points that succeeded lowered from 0.996 (in 2015) to 0.941 in the seasons after the change. A chart in an article on Axios illustrates how dramatic this change has been on extra point success rates.

- In 2023, a new rule allowed offenses to attempt a two point conversion from the 1 yard line (instead of the 2 yard line) when there was a defensive penalty on a touchdown.

- The proportion of two point conversions that succeeded increased from about 0.5 to 0.565, the first season the success rate was well-above 0.5.

The difference of one yard makes a difference. For comparison, attempts to go for it on fourth down and two yards to go succeed 57.2% of the time, and this increases to 65.5% for fourth down and one yard to go.

Decision-making

After a team scores a touchdown, they have essentially two choices. They can kick an extra point or they can attempt a two point conversion. The proportion of extra point attempts that were successful in 2023 was 0.96, and historically the proportion of two-point conversions that have been successful is 0.48. Therefore, on average, the extra point attempt or two-point conversion have promised roughly the same number of points on average.

The goal is not to maximize expected points, it’s to win the game. The two rule changes above have tipped decision-making in favor of the two point conversion in more situations by making the extra point attempt less attractive and the two point conversion more attractive.

The “best” choice for improving the chance of winning is situational and depends on a few factors:

- Point differential

- Time remaining (including time outs remaining)

- Strategies that each team may employ in the resulting situations

- Specific teams and match-ups

The dynamic programming model takes the first two factors into account, where the time remaining is modeled as the number of possessions remaining. Dynamic programming is an algorithmic approach that essentially enumerates the possible outcomes of the remaining drives in the game to quantitively determine the best options for the average team. This approach does not take specific situations into consideration, however, it is informative as a baseline.

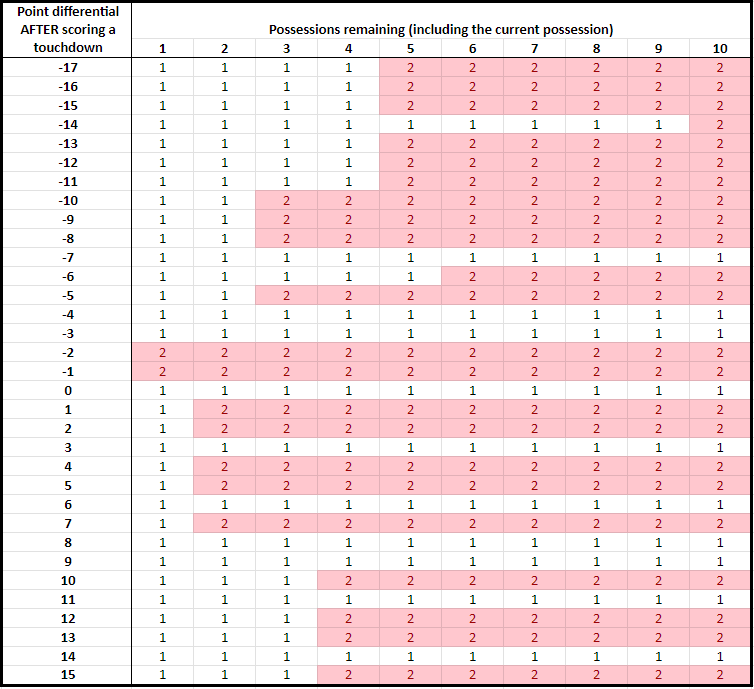

Using 2023 data, I present a chart of when the average team should attempt a two-point conversion based on the 2023 data. In this chart, pictured below, the rows capture the point differential when a touchdown is scored, with a negative score capturing how many points a team is behind. The columns capture how many possessions are remaining in the game, including the current possession. Therefore, as the game evolves, we move left in the table. The team with the final possession of the game has 1 possession remaining in the table, and a team with two possessions left will not get the ball back. Note that there are 22.2 total possessions per game, on average, so the last 6 possessions or so capture the fourth quarter.

According to this chart, an average team should attempt a two point conversion in many situations, including when a touchdown in the fourth quarter puts the team down by 8, 5, 2, or 1 or up by 1, 2, 4, 5, and 7. A team should not go for two when a touchdown puts the team down by 4 or 3, puts the team up by 3 or 6, or ties the game.

Compared to 2014–before the two rule changes mentioned above–two point conversations are now the better choice in more situations. For example, a two point conversation now is the better choice for the average team when a touchdown in the fourth quarter puts the team down by 1.

My analysis, as Prof. Ben Recht notes in an outstanding post on two point conversions, makes a number of assumptions. While some assumptions are more reasonable than others, the model still offers important insights that are not obvious before crunching the numbers.

A better way to decide whether to attempt a two point conversion

When I listen to broadcasts, I get frustrated with the analytics discourse from the commentators, which is often some version of “The analytics tell you to go for 2 in this situation.”

This is wrong. Analytics do not tell people what to do. Analytics are a collection of tools that can inform decision-making, with people making the final decisions.

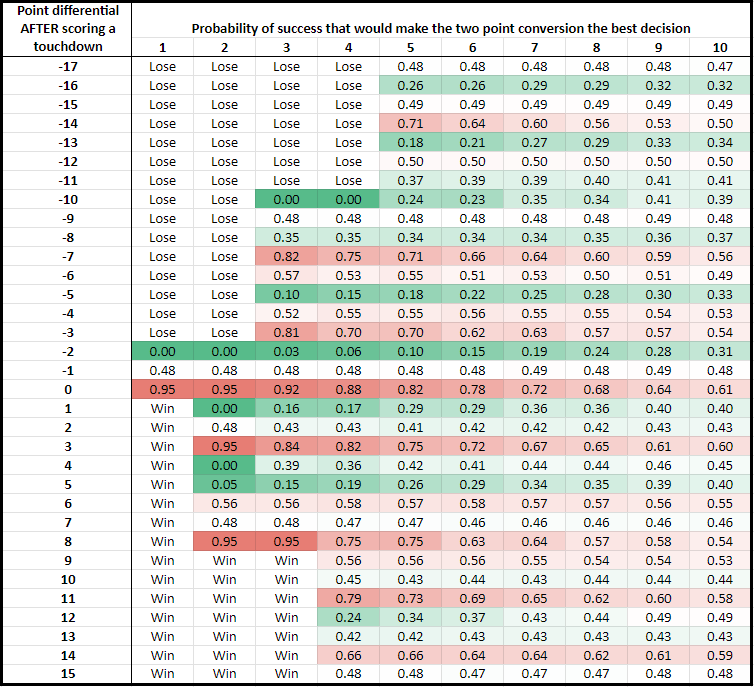

If I were a football coach, I would not use the chart above. I would ask for a different chart based on the same analysis. Below, I create this chart.

No team is the average team. As noted earlier, the analysis using dynamic programming makes some assumptions that are not totally valid, including that an average team is facing an average team. The chart above always gives the same answer for the same point differential and possessions remaining, and it does not reflect other attributes of the situation at hand.

One specific situation that may affect the decision is the play that a team has available for the two point conversion. For example, historically 43.4% of pass plays have succeeded, whereas 61.7% of run plays have succeeded. Having a play in mind–and its associated likelihood of success–should affect the decision. Another situation is the team’s opponent, including their run and pass defense.

There are two ways to make the dynamic programming more informative for specific situations:

- Change the inputs to reflect the current match-up. In this case, one could change the probability that a two point conversion would be successful, the probability that an extra point is successful, the probability that a drive ends in a touchdown, and the probability that a drive ends in a field goal.

- Instead of only reporting the best decision (go for 1 or go for 2), the analysis can be used to report the probability that a two point conversion should be successful for it to be the better choice than attempting an extra point. In this case, a decision-maker (a football coach) can estimate how likely their play would success against the team they are playing in the specific situation they are facing.

I illustrate the second approach below using the dynamic programming analysis above. Instead of reported the binary decision of going for 1 or 2 as before, I report the two point conversion probability of success above which going for two is the better decision. Again, I use data based on average teams. The lower the probability in the chart, the more attractive the two point conversion is.

Some decisions are clear cut. A 0.00 indicates that a team should always go for a two point conversion, and a 0.95 indicates that a team should essentially always attempt the extra point. Most of the probabilities are in between, which means that the “best” decision is not clear cut in most cases.

This new chart is more nuanced than the first chart in this post.

- Sometimes it is obvious to go for 2. A two point conversion is the better decision with a play that has a mere 25% probability of success when a touchdown in the fourth quarter puts the team down by 10, 5, or 2, or up by 1 or 5.

- Sometimes it is obvious to attempt an extra point. Going for two is the better decision with a play with a very high, 75% probability of success, which occurs when a touchdown puts a team down 7 or 3, up 3 or 8, or ties the game. Very few plays can expect a 75% probability of success, so in these situations it almost always is better to attempt the extra point.

Now consider strategies for two different teams:

- Team A with a two point conversion play with a 40% probability of success, and

- Team B with a two point conversion play with a 60% probability of success.

Team A and Team B would make different decisions if a touchdown in the fourth quarter puts them down by 9, 6, 4 or up by 3, 6, or 7.

Another insight: Both Team A and Team B should both attempt a two point conversion if a touchdown puts them down by 8.

Therefore, the same chart yields different “best” solutions for different teams based on the situations at hand. This insight follows directly from the numbers and the modeling, however, it is almost always overlooked in discussions on football analytics.

Related articles and posts:

- When to go for a two point conversion instead of an extra point: a dynamic programming approach (Punk Rock Operations Research)

- The rise of the two point conversion from The Upshot at the New York Times

- When to go for 2, for real from FiveThirtyEight

- Should you go for 2 when down 8? An analysis by Ben Recht

- Should a football team run or pass? A game theory and linear programming approach (Punk Rock Operations Research)

Presidential Punk Rock Operations Research

It was an honor to serve as the President of INFORMS in 2023. During my term, I wrote a president’s column in ORMS Today entitled “Presidential Punk Rock OR.” You can read all of my columns here.

In my last president’s column, I retrospectively summarized my term by the numbers. I’ve reprinted my final column below:

As I write my last “Presidential Punk Rock O.R.” column, I am officially the INFORMS past-president. Now that my term has ended, I have been reflecting on my time as the 2023 INFORMS president, and will summarize my year by the numbers. In 2023, I …

- Chaired 4 Board of Directors meetings held over 9 days

- Worked with 19 board members (as president and president-elect)

- Wrote 4 OR/MS Today print columns

- Including this article, published an additional 9 Presidential Punk Rock O.R. online articles and videos

- Recorded 7 Resoundingly Human podcasts

- Published 2 op-eds (in the Chicago Tribune and The Hill)

- Moderated 1 panel discussion (at the Conference of International Federation of Operational Research Societies (IFORS))

- Participated in 8 briefings with U.S. Senate, House and White House staffers

- Chaired 12 INFORMS Executive Committee meetings

- Attended 2 INFORMS Book Club meetings (and read 5 of the selected books throughout the year)

- Recorded 1 data literacy webinar for policymakers

- Announced 1 Franz Edelman Award winner

- Attended 20 award ceremonies, receptions and meals (12 at the INFORMS Annual Meeting and 8 at the Analytics Conference)

- Wrote 30 INFORMS Connect posts as well as many more posts on LinkedIn and X

- Showed up in approximately 1 gazillion pictures with INFORMS award winners at INFORMS conferences

- Most importantly, met countless members (Although I tried to meet every single member, I did not achieve that goal. Please introduce yourself in 2024 if we have not yet met.)

It has truly been an honor to serve as the 2023 INFORMS president. I look forward to continuing volunteer service to INFORMS and the OR/MS community as the past-president in 2024, and beyond as an INFORMS member. I know 2023 will be hard to beat, but I will keep crunching the numbers and the countless ways INFORMS members are making smarter decisions for a better world.

From ORMS Today

I’m grateful for the countless ways INFORMS members are making smarter decisions for a better world!

New Year Resolutions for 2024

It’s a new year, and I’m reflecting on 2023 and looking forward to 2024. New Years resolutions. As usual, I have set New Year’s resolutions for the coming year. I will continue to focus on self-care and wellness in the coming year. My goals for the year are to continue four habits that I set this past year as well as three new resolutions.

2023 self-assessment. You can review my seven resolutions for 2023 here. In my self-assessment, I did well with physical therapy, public outreach, meditation, and eating leafy green vegetables. I started practicing the piano in the spring and summer and have been on hiatus since then. I hope to return to the piano in 2024. I did not make as much time for writing as I would have liked last year, nor did I master the art of delegation. I hope to do better with both in 2024. Many readers of this blog asked me about how I was doing with leafy greens this past year, and it motivated me to stick with the habit.

Life has many unexpected turns. I am proud two report that I successfully completed two resolutions in 2023 that I never set to begin with. In March, I started a sourdough starter and learned how to bake sourdough (my favorite is an oat and flax loaf), and I’m proud to say that my sourdough starter is still alive. I also joined the INFORMS book club as well as a book club with friends. As a result, I made more time to read for fun than I have in years, although I generally “read” the audiobook versions of the selections to fit reading in my schedule.

My New Year’s resolutions for 2024 are:

- Sleep at least 8 hours per night (at least 5 nights per week).

- Read more for fun.

- Continue to eat leafy greens.

- Write a proposal, a teaching case study, and an op-ed.

- Continue to meditate daily and adjust my practice as needed.

- Do physical therapy and/or yoga (at least 3 days/week).

- Do something every week that scares me.

What are your resolutions? I asked this on X and received a few answers. Answer in a comment below or in X in response to my tweet.

operations research – what is it?

“Operations research – what is it?” is the title of a paper by Philip McCord Morse published in the Journal of Applied Physics in 1952. The paper is a transcript of a lecture Morse gave at the conference on Applications of Operations Research in Industry at Case Institute of Technology, Cleveland, Ohio, November 8-10, 1951. Case Institute of Technology later offered the first degree program in operations research.

Spoiler: Morse declines to define operations research, arguing that “chemistry and physics must have been difficult to define in the early days.” He notes that many definitions of operations research research use the term “quantitative” to reflect its heavy reliance on mathematics. He then goes on to discuss the burgeoning discipline of operations research in great detail.

Morse views operations research as flexible and practical, drawing in all scientific disciplines that existed at the time. He describes operations research as being model-centric and data-driven. In describing operations research, he stresses the importance of:

- collecting data,

- creating mathematical models for prediction and ultimately prescribing courses of action, and

- being experimental, with a feedback loop to continuously improve models to enhance model realism.

Morse describes a general overview of doing operations research. He outlines the process of creating a mathematical model of a physical process, taking care to validate the mathematical model so that it reflects the real process so that solutions to the mathematical model can inform decision-making. He notes that real data informs the creation of mathematical models as well as input parameters, arguing strongly that operations researchers should be familiar with both the data and the application. He alludes to the new discipline of scientific management, where a hands-on approach was common and involved interacting with stakeholders, observing the system, and collecting data.

“The research can only be successful if the operations research group is in frequent, face-to-face contact with the executive in charge of the operation. All the facts about the operations must be available, and usually these cannot be obtained from subordinates. Security restrictions, military or commercial, must not hamper the collection of data”

Morse steps through an example of seeing and attacking German submarines in World War II. The problem started with the British military collecting data on how frequently they were able to attack submarines upon sighting them (40%). The problem became more interesting when the U.S. military also noticed the same observation (40-45%). This led to improved techniques to develop fuses and attack plans, which eventually increased the fraction of sighted submarines successfully bombed to 50%. The next step involved human factors research to train soldiers to better search for aircraft and submarines using their eyes during patrols. All aspects of this application at the time comprised operations research, although human factors and fuse design are now part of other disciplines.

Morse argues that operations research uses other branches of science, including physics, math, biology, psychology, and economics, to solve practical problems. It becomes operations research when it uses data and mathematical models to drive decisions.

Morse notes that game theory was created by operations research groups:

“Operations research has its own branch of mathematics, called the Theory of Games, first developed by von Neumann and since worked on intensively by Project Rand and other military operations research groups.”

A section of the paper is titled “Curiosity unlimited.” While it is evident that Morse views curiosity as an essential part of operations research, what he describes in this section is persistence is solving the problem and the ability to communicate across difference in interdisciplinary teams. He tells an anecdote from his time leading an operations research team in the U.S. military in World War II, when his team made many efforts so that their science-based recommendations would be adopted by military decision-makers.

Morse ends with a discussion of decision-making. Morse does not mention “objective function” although he discusses objectives to practical, mission-oriented problems. It is obvious that he sees the value in operations research in its ability to guide decision-making by harnessing data and using tools from mathematics.

Despite not being given a precise definition of operations research in the article, I left with a sense that early operations research is consistent with the operations research of today.

P.M. Morse (1952). Operations research – what is it? Journal of Applied Physics 23(2), 165-172. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1702167

Related reading:

- on the art of modeling

- operations research was declared dead in 1979

- on George Dantzig, Good Will Hunting, and tackling hard problems

A recap of IFORS 2023

The 23rd Conference of the International Federation of Operational Research Societies (IFORS) was held in Santiago, Chile on July 10-14, 2023. I attended and enjoyed the conference talks and conversations. I appreciate the efforts of the organizing and program committees, especially co-chairs Jorge Vera and Rafael Epstein as well as program chair Alice Smith. Here are a few highlights of the conference.

In the opening plenary entitled “From Academia to Politics: A Vision for Addressing Urban Transport Sustainability Based on Lessons from Santiago’s Transport System,” Juan Carlos Muñoz addressed the modernization of Santiago’s public transportation system. The challenges were technical and political, and they included route optimization, seamless fare collection, and sustainability. Muñoz noted that Santiago has more electric buses in their fleet in any city outside of China. He outlined several stories and challenges at the intersection of transportation logistics and politics, including an interesting story summarized how the public transportation system supports the citizens’ ability to vote. There are many performance goals, and the one I like above all was summarized by Juan Carlos Muñoz as “Earning the heart of Santiago’s citizens.”

Margaret Brandeau gave the second plenary talk entitled “Advancing Analytics for Better Health and a Better World.” She told several stories about her research for social good, including how to allocate limited COVID-19 vaccines, policies for homelessness, policies for the opioid epidemic (prevention, treatment, diversion, etc.), and the effect of climate change on crop nutrition. Professor Brandeau made it clear that she has enjoyed influencing policy in recent years, and she argued for greater usage of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare. One of her research stories motivated early analyses for influencing policy by developing simple but insightful mathematical models using small amounts of available data without waiting for having having a large amount of data. When the talk concluded, I had a greater appreciation for the simple yet informative models we can create and analyze. You do not need big data to make a difference.

Paulo Toth gave the third plenary talk entitled “Metaheuristic Algorithms for Location-Routing Problems.” Andreas Weintraub gave the final plenary talk entitled “How OR has Impacted Decisions in Natural Resources.” Rene de Koster, Tava Olsen, Andrea Lodi, and Dolores Romero Morales, Brian Denton, and Anna Nagurney gave the keynote talks.

There were several special tracks, including a session by Leonardo Bassi about the 2022 Franz Edelman Award awarded to the Chilean Ministries of Heath and Sciences: Analytics Saved Lives during the Covid-19 Crisis in Chile.

I organized a panel discussion about AI entitled “Opportunities at the Artificial Intelligence / Operations Research Interface” with panelists Michael Fu, David Shmoys, Lavanya Marla, and Ahmed Abbasi. In the panel, we discussed aspects of AI amenable to OR methods, fairness, risks of AI, the impact of generative AI, and how OR curricula should be adapted to train the next generation in AI. I plan to follow up on this. Stay tuned.

What is your American gladiatOR name?

The documentary series “Muscles & Mayhem: An Unauthorized Story of American Gladiators,” which was released by Netflix this month, has reminded me of the television reality show American Gladiators that debuted in 1989. The television show featured amateur athletes who participated in various strength and agility challenges in competition against each other and the show’s so-called “gladiators.” The gladiators used stage names on the show such as Nitro, Laser, Lace, Blaze, Ice, and Turbo.

What is the connection to operations research? There isn’t one, at least not exactly. Bear with me.

I haven’t thought about American Gladiators in the last 30 years. Now when I reminisce over the show, I notice the “OR” at the end of “gladiatOR.” As a result, I find myself thinking about operations research inspired gladiatOR names that have one or two syllables in the style of the names used on the television show (only a couple of gladiators had three syllable names, such as Malibu and Gemini).

A gladiatOR name has one or two syllables and has a connection to operations research. Here are a few possibilities:

- Arc

- Random

- Simplex

- Cutter

- Bound

- Fathom

- Edge

- Cone

- Robust

- Convex

What is your gladiatOR name?

Related post:

on George Dantzig, Good Will Hunting, and tackling hard problems

George Dantzig invented the simplex algorithm and contributed to linear programming. He introduced the world to the power of optimization, which has led to massive increases in productivity and drives the global economy (Read more in Prof. John Birge’s article here).

The movie “Good Will Hunting” has a scene that is inspired by the life of George Dantzig. In the movie, Matt Damon plays an MIT janitor who anonymously solves a difficult math problem that a math professor posted on a hallway blackboard.

In real life, George Dantzig once arrived to Jerzy Neyman’s class late while he was a graduate student at the University of California-Berkeley. He wrote down what be believed were two homework problems posted on the blackboard, not knowing that the problems were unsolved math problems, because he had missed the announcement at the beginning of class. he then solved the problems, apologizing to Prof. Neyman that it took so longer to do the homework. They later became the foundation of his thesis. Read more here.

“If I had known that the problems were not homework but were in fact two famous unsolved problems in statistics, I probably would not have thought positively, would have become discouraged, and would never have solved them,”

George Dantzig

I like this story. I also like Good Will Hunting and recommend it without hesitation.

I reflected on this story after returning from the 2023 INFORMS Analytics Conference.

I have always been impressed by how the operations research community has never shied away from hard problems in theory, computation or practice. The operations research community has been tackling hard problems since its early days during World War II, prior to George Dantzig’s solutions to the (then) unsolved problems in statistics.

We are still at it.

Our dedication to solving hard problems is evident at the Edelman Gala at the INFORMS Analytics Meeting, from which I recently returned (watch this year’s gala here). The Edelman Gala celebrates achievements in operations research and analytics, and it awards the Franz Edelman Award and the Daniel H. Wagner Prize. These prizes recognize the application and implementation of solutions that have made a big difference. The finalists of these awards embody the spirit of George Dantzig, and they reinforce that we solve problems and make a real difference in the world.

What do you call a group of operations researchers?

A gaggle of geese.

A murder of crows.

A parliament of owls.

A flamboyance of flamingos.

A pride of lions.

What do you call a group of operations researchers?

I asked this question to the OR community on the INFORMS Open Forum. Here are some of the answers I received:

- A tableau of optimizers (from Ralph Asher)

- A distribution of problem solvers (from Anthony Bonifonte)

- A model of operations researchers (David Tullet)

- A process of industrial engineers

- A sequence of analysts (from Kara Tucker)

- A quantity of quants (from Paul Rubin)

- A queue of operations researchers (from Greg Godfrey)

- A simplex of operations researchers (from Tallys Yunes)

What is your answer?

collaborating on academic research: a discussion with PhD students

In my last lab meeting with the five PhD students in my lab, we discussed how to collaborate on research. While I have a lab compact conveying my expectations for myself and students who work under my supervision, the lab compact focuses more on individual expectations rather than collaboration. I decided to give collaboration more attention.

As a group, we collaboratively edited a document in real-time that outlines techniques that various lab members have found to be effective in their collaborations. Most of their collaborations are with me, their advisor, and sometimes a co-advisor. Several items on the list sparked deeper discussions, which we will explore in more detail in further lab meetings. Here is our preliminary list of how to collaborate on academic research:

- Write papers as you research (not all at the end)

- There are many different ways to do this, so this topic would benefit from further discussion.

- Structure the results section of your papers around key figures that tell the story. Restructure the earlier sections of the paper as necessary

- Document research as you research (and share with collaborators at meetings)

- Create PowerPoint presentations as you do research to stay organized, summarize progress, share weekly progress, track milestones, and document main results

- Create text files after each meeting to summarize discussion and next steps

- Keep a lab notebook

- Write down what you complete every day so you can track your own progress.

- Learn how to create figures to communicate research concepts and models to others (This is hard)

- When you see research talks, notice good figures and emulate them

- Share files for collaborative writing

- Overleaf

- OneDrive

- Zotero – created shared set of papers (make corrections to BibTeX entries)

- Version Control – Github /Github Desktop

- Task Management / tracking project progress

- Trello boards / Todoist boards / Notion / Obsidian

- File management. Create a folder for each paper.

- We will dig into this in a future lab meeting